Defining Bullying, Inspiring Kindness

“You’re being such a bully!” These are familiar words to any parent, and they are more familiar words to any parent with more than one child. If your kids are like mine, calling a sibling, or anyone else for that matter, a bully is a way to get an immediate response out of an adult. But often this word can be overused to the detriment of kids’ social maturity. Once this year an elementary student used a potty word at the lunch table, and when I approached the group, all the other boys were pointing fingers at him and saying, “You’re a bully! Yeah, he’s bullying us!” In this last piece on our CommUNITY week content, I’ll address the issue of bullying. What is it, and what’s one way we can stop it?

As teachers have worked with our elementary students on the language of community, one of the issues we have addressed is the difference between being rude, being mean, and bullying. This conversation was inspired by an article we were passing around earlier this year by Signe Whitson. Here is how she defines the terms:

Being Rude. Inadvertently saying or doing something that hurts someone else.

Being Mean. Purposefully saying or doing something to hurt someone once (or maybe twice).

Being a Bully. Intentionally aggressive behavior, repeated over time, that involves an imbalance of power.

In being familiar with these definitions, kids can more easily determine whether or not a problem is a “big” problem or a “small” problem. With a big problem, kids need to tell a trusted adult. Bullying is absolutely such a problem. If a student is being repeatedly picked on, verbally, physically, or online, parents should be brought into the discussion.

But in many cases, conflicts are on the level of rude. In the case above, a student used a potty word at the lunch table. Given what I soon found out about the situation, this was an instance of being rude. While potty words are not accepted at MAK, the kids at the table could have followed Kelso’s lead and “talked it out,” telling their friend to watch his language. But immediately accusing him of being a bully suddenly brings an adult into the conversation, and instead of learning to solve the problem, now the students involved have become dependent on an adult for their conflict resolution.

In this situation, the best response is likely to ask some questions to help guide their thinking. Was your friend really being a bully here? Or was he being mean or rude? What did you guys do to help solve this problem? By helping kids define the scope of their problem, we can help them better find solutions that will help them grow in their character.

In this situation, the best response is likely to ask some questions to help guide their thinking. Was your friend really being a bully here? Or was he being mean or rude? What did you guys do to help solve this problem? By helping kids define the scope of their problem, we can help them better find solutions that will help them grow in their character.

But talking about problems is not the only approach. In fact, it’s only half the story. Throughout our week on this issue, our major focus was on positive behavior, which for us is the best antidote to being rude, being mean, or being a bully. If kids can understand the benefits of being kind, and not just the consequences of being mean, kindness can be contagious.

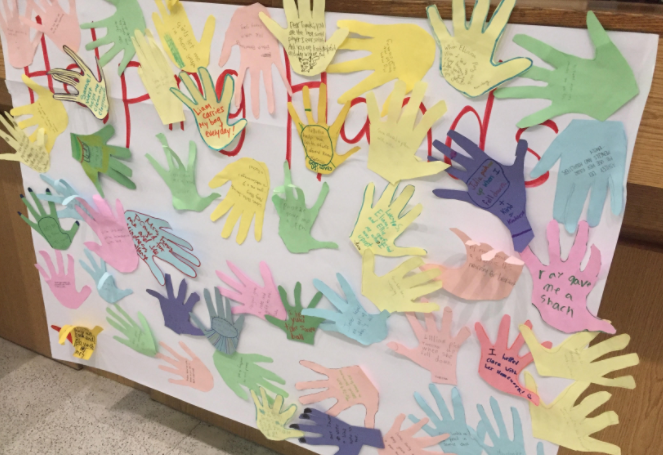

Thus, our week included major promotion of being proactively kind. This included a door decoration contest about kindness, a poster of handprints celebrating kind acts, and a lunchtime flash mob by our elementary teachers and staff. But being kind isn’t just a matter of inspiration; it often has to be practiced and learned.

Even after our CommUNITY Week, students are still carrying out the Great Kindness Challenge. Here students are encouraged to complete 50 acts of kindness at home and at school, learning the discipline of kindness. Students who complete the challenge will be able to put their handprint on the hallway walls of the elementary school, along with their name and year.

At MAK it’s our hope not only to help kids build the language necessary to live responsibly, respectfully, and safely, but also to inspire and teach them to be proactively kind to their neighbors.